The Legislature and Governor Pawlenty Disagreed on the Role of Taxes in Resolving the State's Budget Shortfall

The primary challenge of the 2009 Legislative Session was to address Minnesota’s considerable $6.4 billion budget deficit for the upcoming two-year budget cycle (the FY 2010-11 biennium).[1] This deficit equals 17 percent of the state’s general fund. Increased federal funding for health care contained in the economic recovery act reduced the shortfall to a still daunting $4.6 billion.

When facing a budget shortfall, the state has three primary tools it can use: raising revenues, cutting spending and using one-time measures. In the 2009 Legislative Session, policymakers had to determine how much tax increases would be part of the solution to the state’s shortfall, and also whether to make changes to the “aids and credits” portion of the budget, which includes state aid to cities, counties and towns, as well as tax credits and deductions available to taxpayers. Including tax increases as part of the deficit solution would allow policymakers to balance the budget without making as deep of cuts into critical services as otherwise would be necessary.

Policymakers were making these decisions in a context where Minnesota’s tax system is a smaller share of the economy than a decade ago. The average share of income that Minnesotans pay in state and local taxes dropped by 13 percent from 1996 to 2006.[2]

The rising regressivity of Minnesota’s state and local tax system was also a concern to many policymakers. When a tax system is regressive, low- and middle-income people pay a larger share of their incomes in taxes than those with the highest incomes. In 2006, the wealthiest one percent of Minnesota households — those with incomes over $448,000 — paid 8.9 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes, compared to the average of 11.2 percent.[3]

The Legislature and Governor Pawlenty had a strong difference of opinion on these questions, and ultimately did not come to agreement before the end of the 2009 Legislative Session. The Governor then chose to end negotiations and resolve the $2.7 billion state budget shortfall that remained at the end of session through unilateral action under the unallotment process.

This document evaluates how proposals in the major tax areas would address the two critical questions raised above: how much revenue our tax system will raise, and what degree of fairness there will be. It compares the Governor’s budget, the Senate omnibus tax bill, the House omnibus tax bill, final tax legislation passed by the Legislature, and the Governor’s unallotment plan.

What Was Proposed and What Passed?

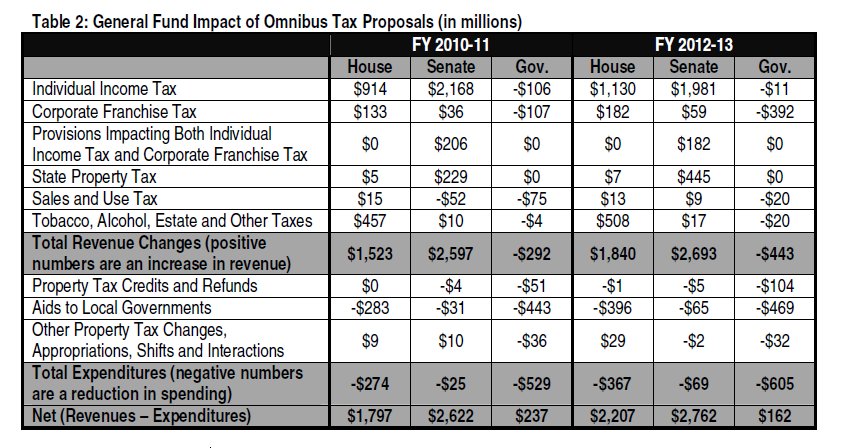

In his budget, the Governor proposed a package of new tax cuts and deep cuts to aids and credits that would have shaved $237 million off the budget shortfall.[4] (In contrast, the Senate’s tax plan reduced the deficit by $2.6 billion and the House’s by $1.8 billion.) The Governor proposed $292 million in tax cuts, with the largest item being cutting the corporate tax rate in half.

The Governor proposed the largest cuts to aids and credits and other tax expenditures. His budget would have cut $529 million in this area in FY 2010-11, making deep cuts to aids to counties and cities and property tax credits to renters. A significant portion of these reductions would have been used to pay for the new tax cuts. In contrast, the House omnibus tax bill proposed cutting aids and credits by $274 million and the Senate by $25 million.

The Minnesota House and Senate each passed omnibus tax bills that increased taxes, but also made some cuts to aids and credits, as part of a balanced approach to resolving the state’s budget shortfall. These bills also sought to reverse the rising regressivity of the state’s tax system. Both the House and Senate put an emphasis on the income tax, the only one of the state’s major taxes based on ability to pay, and each proposed a new fourth income tax bracket on the highest-income households. The Senate also proposed increasing income tax rates on the existing three brackets. The House omnibus tax bill repealed a range of income and corporate tax credits and deductions and raised taxes on tobacco products and alcoholic beverages.

The differences between the House and Senate omnibus tax bills needed to be resolved through a conference committee. The tax conference committee process produced three tax bills:

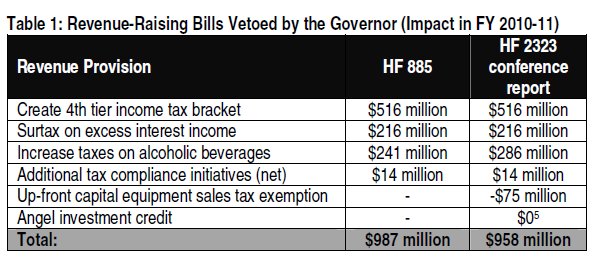

- On May 8, several items under consideration in the tax conference committee were passed by the Legislature as HF 885. This bill included a new income tax rate on the highest-income Minnesotans, increases in alcohol taxes, a surtax on income raised through excess interest rates, and increased tax compliance initiatives. This bill was vetoed by the Governor.

- On May 12, tax provisions that were noncontroversial and had little fiscal impact were passed as HF 1298. This bill was signed by the Governor.

- In the final moments of the legislative session, the tax conference committee completed a brief conference committee report on HF 2323, which included increases in the same three tax areas as in HF 885, but also included two tax cuts and a payment shift for school funding. This bill was passed by the Legislature but also vetoed by the Governor.

Governor Pawlenty Closes Deficit through Unallotment

The fact that the Governor and Legislature were unable to come to a negotiated compromise meant that the legislative session ended with $2.7 billion of the FY 2010-11 deficit unresolved. Governor Pawlenty used his unallotment authority to unilaterally make spending cuts and timing shifts to balance the budget. The Governor’s unallotment plan uses $572 million in changes in taxes and aids and credits to balance the budget. The major provisions include:

- Raising $106 million in FY 2010-11 by asking the State of Wisconsin to reimburse the State of Minnesota sooner under an existing reciprocity agreement. Under the agreement, Wisconsin residents who work in Minnesota file their state income taxes in Wisconsin, and Wisconsin remits those taxes to Minnesota, and visa versa. There is currently a 17-month delay in receiving those payments. (Since the Governor announced his unallotment plan, the reciprocity agreement has been ended altogether, raising an estimated $131 million.)

- Delaying $63 million in refunds for business purchases of capital equipment that occur at the end of FY 2011 by up to three months.

- Delaying $42 million in corporate tax refunds that occur at the end of FY 2011 for up to three months.

- Eliminating the Political Contribution Refund (PCR) for the FY 2010-11 biennium. The PCR is a component of the state’s campaign finance system that provides refunds for small donations to candidates or political parties.

- Cutting the Renters’ Credit, a state property tax refund for low- and moderate-income renters, by $51 million in FY 2011.

- Cutting $300 million from aids to local governments.

Unallotment Does Not Settle the Debate

The Governor’s unallotment decisions are only in effect for FY 2010-11, and the state’s budget shortfalls are ongoing. The debate about taxes in Minnesota will continue, and proposals like those put forward this year are likely to be part of the discussion in future legislative sessions.

Looking at the Details

Proposals in each major tax area are described below, comparing the Governor’s budget, Senate omnibus tax bill (SF 2074) and House omnibus tax bill (HF 2323), as summarized in Table 2. The final tax legislation passed by the Legislature and the Governor’s unallotment plan are also described.

Income Taxes

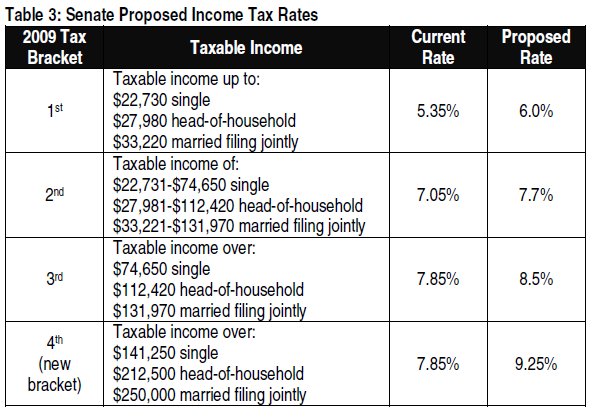

Both the House and Senate proposed using the income tax as the primary means for raising revenues in their omnibus tax bills, with the House raising $914 million in FY 2010-11 through the income tax and the Senate $2.2 billion. Both the House and Senate proposed creating a new fourth income tax bracket in order to address the fact that the highest-income Minnesotans pay a smaller share of their incomes in total state and local taxes than other Minnesotans. The Senate created a new 9.25 percent tax rate on taxable income over $250,000 for a married couple. The House proposed a nine percent tax rate on taxable income over $300,000 for a married couple, which would have raised $470 million in FY 2010-11.[6]

In the course of the debate, questions were raised as to how small businesses would be impacted by the creation of a fourth tier income tax bracket. An analysis by the Minnesota Department of Revenue found that only 5.7 percent of households with small business income would pay any additional taxes due to a new income tax rate on $250,000 of taxable income for married couples.[7]

The Senate also proposed to increase income tax rates in the existing three brackets, as Table 3 illustrates. These rate changes are sometimes described as "rolling back" the rates to where they were in 1998, before the income tax rate cuts made in 1999 and 2000. The Senate proposal would have returned income tax rates to the levels in effect in 1998 for the first and third bracket. The new rate in the second bracket would have been less than the 8.0 percent rate existing in 1998.

The Senate’s new fourth income tax bracket and the other income tax rate increases together would have raised $2.2 billion in FY 2010-11, or 84 percent of the revenue raised in the Senate omnibus tax bill. The rate changes and the new fourth income tax bracket were temporary, and would have blinked off once they were no longer needed to balance the state’s budget.[8]

The compromise tax bills passed by the legislature (HF 885 and the HF 2323 conference report) created a hybrid between the House and Senate approaches for a fourth tier income tax: a 9.0 percent rate on taxable income over $250,000 for a married couple, raising $516 million. This rate would have expired after tax year 2013 if the 2013 February forecast showed a surplus of at least $500 million. The remaining tax brackets were unchanged. But these bills were vetoed by the Governor, and no changes to income tax rates were passed into law this year.

The House proposed raising a net of $544 million in FY 2010-11 by eliminating many income tax deductions and credits (often called "tax expenditures"), and replacing some of them with three new credits. The itemized deductions for mortgage interest and charitable giving would have been eliminated but replaced with new credits, making the tax benefit available to more taxpayers, not just those who itemize. But the statewide total amount of tax reduction provided by the new mortgage interest credit and the charitable giving credit would have been smaller than what is now provided through those deductions.

The K-12 education credit and child and dependent care credit would also have been eliminated, but replaced with a new Minnesota Child Credit for low- and moderate-income families of up to $200 per child, and an increase in funding for basic sliding fee child care assistance. Other deductions and credits that would have been eliminated under this proposal include the federal itemized deduction for real property taxes, K-12 expense deduction and the lower-income motor fuels credit.[9]

The Senate proposed just a few changes to income tax deductions and credits. It repealed the low-income motor fuels tax credit and eliminated the tax deduction for mortgage interest paid on a second home, which together would have raised $201 million in FY 2010-11.

None of these proposed changes to income tax deductions and credits were passed in the 2009 Legislative Session. However, the Governor eliminates the Political Contribution Refund (PCR) for the FY 2010-11 biennium under unallotment. The PCR provides a refund of up to $50 per individual for qualified donations to state political parties or candidates. This action saves the state $10 million, and had been proposed in the Governor’s budget.

Each year the state must decide whether to conform Minnesota’s tax law to recent federal tax changes. Some federal conformity provisions affecting tax year 2009 moved separately from the larger tax discussion as HF 392. During the remainder of the legislative session, several federal conformity provisions related to the income tax remained under consideration, including the exclusion of up to $2,400 of unemployment compensation from income taxes in tax year 2009. The Governor, House and Senate adopted this provision, which would have resulted in a one-time cost of $28 million in FY 2010-11. However, this provision was not included in HF 1298, which contained the remainder of the tax conformity items that became law this year.

Corporate Taxes and Other Taxes on Business Income

The Governor, House and Senate took very different approaches to corporate taxes and other taxes on business income. (Some businesses pay taxes on their profits through the corporate tax, while others pay their taxes through their owners’ or shareholders’ individual income taxes.)

The Governor proposed cutting corporate taxes by $103 million in FY 2010-11, while the Senate would have raised them by $26 million and the House by $127 million. The Senate proposed raising an additional $216 million in income and corporate taxes through a provision to raise taxes on income earned by charging interest higher than 15 percent. This provision was included in the two compromise tax bills that were vetoed by the Governor.

The largest of the Governor’s proposed tax cuts would have cut the state’s corporate tax rate in half over six years, costing the state $100 million in FY 2010-11, $390 million in FY 2012-13 and more in future years.

The House and Senate did not propose changes to the corporate tax rate, but they did propose changes to what income is subject to tax – in some cases, closing some special preferences, in other cases providing new exemptions.

The House included proposals to address items they consider business tax preferences that benefit only certain kinds of businesses. This included repealing Foreign Operation Corporations, the foreign royalty subtraction, changing treatment of corporate income related to tax havens, creating an addback for Minnesota development subsides, and ending income tax and corporate tax exemptions under the JOBZ program. Because of the changes to JOBZ, the House would have allowed businesses to withdraw or renegotiate their JOBZ agreements. (The Senate proposal would not have allowed any new JOBZ designations after April 30, 2009, which would have raised $4 million in FY 2010-11.)

In exchange for eliminating preferences for particular businesses, the House proposed two tax changes aimed at helping a wider range of businesses, called Single Sales Factor and Section 179 expensing. The House (and Governor) proposed conforming to federal changes to Section 179 expensing, which allows businesses to deduct more of the cost of capital equipment from taxes in the year the equipment is put into service, rather than spreading out that deduction over many years. This proposal would have meant a $22 million tax reduction in FY 2010-11.[10]

Single Sales Factor relates to the way that a multistate business is subject to tax. Many states use a three-factor formula to determine what portion of a multistate corporation’s income is subject to the state’s corporate income tax. Minnesota previously had an apportionment formula that was based 75 percent on the amount of a corporation’s sales made in the state and 12.5 percent each on the share of a company’s property and payroll in the state. Legislation passed in 2005 is changing this formula over an eight-year period so that by 2014, apportionment will be based completely on sales (a “Single Sales Factor” formula). The House proposed speeding up the process so that Single Sales Factor would have been in place for tax year 2009, which would have cut corporate taxes by $58 million in FY 2010-11.

The Governor did not propose any changes to current law, while the Senate took an entirely different approach. The Senate omnibus tax bill froze the state’s transition to Single Sales Factor, so that apportionment would be based 81 percent on sales. This would have raised $26 million in FY 2010-11.

Although proponents argue that the Single Sales Factor formula will help businesses, in fact, some Minnesota corporations would see a tax cut and others would experience a tax increase. Fiscal analysts with the House of Representatives found that had Single Sales Factor been in place in 2004, just nine percent of corporations who file corporate taxes in Minnesota, or 4,500 corporations, would see a tax cut.[11] But 13 percent, or 6,500 corporations, would pay higher taxes under Single Sales Factor. The majority of corporations would see no impact. Generally, companies with production facilities concentrated in Minnesota but who sell to a national market benefit from Single Sales Factor, but tax increases would fall on manufacturing companies with a significant amount of sales in Minnesota but small amounts of their total production facilities and employees located in the state.

No changes to corporate tax rates or the apportionment formula were passed into law in 2009. However, under unallotment, payments of corporate tax refunds that occur at the end of FY 2011 will be delayed by up to three months, moving $42 million of state costs from FY 2011 into FY 2012.

The Senate omnibus tax bill created a new surtax on excess interest income, raising an estimated $216 million in FY 2010-11. For transactions with an interest rate over 15 percent, this would have imposed a 30 percent tax on the portion of income generated by interest that exceeds 15 percent. As mentioned above, this provision was included in the two compromise tax bills that were vetoed by the Governor.

The Senate would have created a new exemption from the income tax of 10 percent of pass-through income (from partnerships and S-Corporations) for four years. Under existing tax rates, the exemption would have amounted to a $160 million tax cut in FY 2010-11. Taking into account the higher tax rates proposed in the Senate’s bill increases the proposed tax cut to $184 million.

The Governor, House and Senate all included proposals to provide tax incentives for investors and business investment. Some examples include:

- The Governor created a new Green JOBZ initiative to provide twelve years of tax incentives for companies that “create renewable energy, represent manufacturing equipment or services used in renewable energy, or that create a product or service that lessens energy use or emissions.”

- The House expanded the Research and Development Credit and allowed it to be taken on the individual income tax.

One such provision – an angel investment credit – was included in the HF 2323 conference report. This legislation was vetoed by the Governor, and no major changes to business tax incentives were passed into law this year.

Alcohol and Tobacco Taxes

The House proposed tax increases on alcohol and tobacco products that would have raised a cumulative $420 million in FY 2010-11. Tobacco and alcoholic beverage excise taxes are set at a certain number of cents per unit. In this way they differ from the general sales tax, which is a percentage of the sales price. As a result, tobacco and alcohol excise taxes do not automatically increase as prices rise with inflation. Alcoholic beverage excise tax rates have not been raised since 1987.

The House raised $211 million in tobacco taxes through a 54 cent a pack increase on cigarettes and changes to other tobacco taxes. Another $209 million would have been raised by a proposed increase in the gross receipts tax paid on alcoholic beverages at the retail level from 2.5 percent to five percent, and increasing the alcoholic beverage excise tax by about a penny a drink for most kinds of alcohol and about three cents a drink for distilled spirits.

HF 885 and the tax conference committee report raised $241 million and $286 million respectively through modified versions of the House’s alcohol tax proposals. But these bills were vetoed by the Governor, so no changes to these taxes were passed in 2009.

General Sales Taxes

There were few proposed changes to the general sales tax this session. One perennial topic that was again discussed this year was the tax exemption for business purchases of capital equipment. Many tax experts argue that sales taxes should apply only to the final purchase of a product by the consumer and not be collected on the materials used by a business to create the final product. Under current Minnesota law, purchases of capital equipment by businesses are exempt from the sales tax. However, a business must pay the sales tax when they purchase capital equipment and then apply for a refund. The Senate and Governor proposed allowing businesses to receive the tax exemption when they purchase their capital equipment. This proposal would have cost the state $75 million in FY 2010-11, but only $20 million in FY 2012-13. This is because the change primarily impacted the timing of when the tax exemption is received. This provision was also included in the tax conference committee report that was vetoed by the Governor.

The House and Senate both attempted to level the playing field between online and “bricks and mortar” businesses. The Senate and House omnibus tax bills included a provision to expand the definition of business nexus to enable sales tax collection on some purchases made on the internet. This change would have only applied to out-of-state businesses that contract with a Minnesota person or company to advertise its business in Minnesota. This would have raised an estimated $23 million in FY 2010-11. The House omnibus tax bill also expanded the state sales tax to include digital downloads (such as downloads from iTunes), which would have raised about $4 million in FY 2010-11.

The House also proposed narrowing the current sales tax exemption on electricity and natural gas used for home heating. Currently these purchases are exempt from sales tax from November through April. This provision would have collected the tax once an above-average amount of usage has been exceeded, raising $34 million in FY 2010-11.

None of the proposed changes to the general sales tax were passed into law in 2009. However, under unallotment, the payment of capital equipment sales tax refunds will be temporarily delayed by up to three months, shifting $63 million in refund payments from FY 2011 into FY 2012.

Property Taxes

Property taxes are primarily a revenue source for local governments, not the state. However, the state influences property taxes in several ways. The state provides property tax credits directly to taxpayers. The state also provides aid to local governments, with the goal of lowering property taxes and ensuring that even local governments with low property wealth can provide a basic level of service. And the state sets parameters about how property taxes are determined on various types of properties and limits how much local governments may raise in total property taxes.

From 2002 to 2009, homestead property taxes grew by around 39 percent, after adjusting for inflation,[12] and increased reliance on local property taxes is one of the contributors to increased inequity in the state’s tax system. Given this trend, policymakers have put more focus on property taxes in recent years.

The Governor proposed deep cuts to the “aids and credits” portion of the tax budget. This includes aids to local governments as well as the state’s Property Tax Refund for renters. The House omnibus tax bill proposed significant cuts in local government aid, though less than the Governor. The House would have also given local governments more flexibility in mandated spending and in local revenue-raising. The Senate proposed cutting aids to local governments much less than the House or Governor. The House and Senate also rejected the Governor’s proposed cuts to the Renters’ Credit.

The Legislature did not enact any cuts to this portion of the budget, but under unallotment, the Governor will implement his proposed cut to the Renters’ Credit as well as a $300 million cut to aids and credits to local governments.

Although property taxes are largely a local funding source, the state uses tax credits and refunds to reduce property taxes for certain taxpayers. There are two primary property tax credits that lower property taxes for Minnesota households.

- The Property Tax Refund (PTR) is a refundable credit for homeowners and renters below certain income limits whose property taxes are high in comparison to their income. The PTR for homeowners is commonly called the Circuit Breaker, and the PTR for renters is called the Renters’ Credit.

- The Homestead Market Value Credit directly reduces a homeowner’s property taxes through a credit on the property tax bill. The state normally reimburses the locality for the lost revenue. (There is also a similar Agricultural Market Value Credit.)

The House proposal would have reduced the Market Value Credit, which is based on home value, and increased the Circuit Breaker, which is based more on household income. The House proposed increasing the Circuit Breaker by $19 million. This is a six percent increase, and it would have been achieved through two changes:

- Increasing the maximum amount of credit by 10 percent.

- Making it a little easier for households with incomes between $18,120 and $67,909 to qualify, and providing these households with a larger credit.

The Senate proposed eliminating the targeted property tax refund, which provides a refund for homeowners whose property taxes grow significantly in one year. Unlike the Circuit Breaker, the targeted property tax refund has no income limit to qualify. This proposal would have saved $4 million in FY 2010-11.

No major changes to the Circuit Breaker or Market Value Credit were passed in the 2009 Legislative Session.

In his budget, the Governor proposed cutting the Renters’ Credit by 27 percent, which amounted to a $51 million cut in FY 2010-11 and a $104 million cut in FY 2012-13. The Renters’ Credit recognizes that, although the owners of rental properties are legally responsible for paying the taxes on that property, a portion of the tax is passed on to renters in the form of higher rent. The Renters’ Credit helps minimize the impact of rental property taxes – among the most regressive taxes in Minnesota – on low- and moderate-income households.

The House and Senate rejected the Governor’s proposal to cut the Renters’ Credit. However, the Governor is implementing his proposed cut to the Renters’ Credit in FY 2011 only. Nearly 281,000 Minnesota households will see a cut in their Renters’ Credit, the average Renters’ Credit will be reduced by $163, and 18,200 households will lose their Renters’ Credit completely. Twenty-eight percent of households receiving the Renters’ Credit include seniors or people with severe disabilities.

During a recession, financial assistance to low-income families is one of the most effective economic stimulus tools the government has because these individuals are likely to spend those dollars quickly and locally. The Renters’ Credit is one of these tools.

The state provides general aid to local governments in order to reduce local property taxes and to ensure that all local governments — regardless of their level of local property tax wealth — have sufficient revenues to provide adequate services. These aids come through two primary funding streams.

- In 2008, 93 percent of Minnesota cities received such assistance through Local Government Aid (LGA). LGA is distributed through a formula that tries to take into account a city’s ability to raise revenues locally and local needs.

- All of Minnesota’s 87 counties receive general state aid through County Program Aid.

Aids to local governments have seen significant changes over time as the state has faced large budget deficits. For example, aids to local governments in the FY 2004-05 biennium were cut by about a quarter compared to base funding during the 2003 Legislative Session. In December 2008, the Governor used unallotment to cut Local Government Aid and County Program Aid for FY 2009 by $98 million.

In addition, the state reimburses local governments for the lost revenues from the Market Value Credit (MVC). While not a state aid in the same way the state provides assistance through LGA or County Program Aid, this is another way that the state provides funding to local governments, and here too cuts have been made. The MVC was cut by $13 million for FY 2009 under unallotment actions taken by the Governor in December 2008.

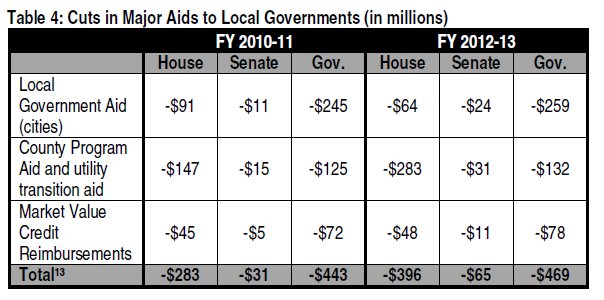

Table 4 summarizes the proposed cuts in state aid to local governments. The Governor proposed the deepest cuts: a cumulative cut of $443 million in FY 2010-11 and $469 million in FY 2012-13. Under his budget, County Program Aid was cut by 27 percent and Local Government Aid by 23 percent, compared to base funding. The $125 million reduction in County Program Aid assumed that counties would earn back a significant portion of a larger $183 million cut by moving towards regional human service delivery. The Governor also proposed cutting reimbursements for the Homestead Market Value Credit by 13 percent.

The House also proposed cutting aids to local governments significantly: $283 million in FY 2010-11 and $396 million in FY 2012-13. Counties would have faced deeper cuts in County Program Aid in the FY 2012-13 biennium than proposed by the Governor, but the House proposed giving counties the option of raising a 0.5 percent sales tax, as well as a $20 per vehicle excise tax on motor vehicle sales made in the county.[14] If the county did not enact a local sales tax, the cut in County Program Aid would have been 3.58 percent of their total levy plus aid. The Senate proposed the least cuts to aids to local governments.

The legislative session ended without any agreed-upon changes to aids to local governments. The Governor’s unallotment plan includes $300 million in cuts to aids to local governments. One-third of the reductions will be to counties and the remainder to cities and townships.

The total amount of property taxes raised by a local unit of government is called its levy. At times the state has put in place levy limits, which limits how much the levy can grow from year to year. In 2008, the Legislature and Governor agreed to increase aids to local governments — restoring some of what was cut in 2003 and 2004 — but also instituted levy limits. Many lawmakers argued that once the Governor cut local aids through unallotment in December 2008 and proposed deeper cuts in his budget, that deal had been broken and therefore levy limits should also be lifted. The Senate would have lifted levy limits on both cities and counties. The House would have lifted levy limits on cities in 2009 and on counties in 2010. None of these changes were passed into law this legislative session.

While property taxes are primarily a local funding source, commercial, industrial, most public utilities, cabin and unmined iron ore properties are subject to a state property tax. Currently, the total amount raised by the state property tax grows by the rate of inflation each year. In addition to the inflationary increase, the Senate proposed increasing the state property tax paid by $229 million in FY 2010-11 and $445 million in FY 2012-13 by freezing the tax rate at 2003 levels, instead of letting it fall as it would under current law. It would also have exempted cabins from the state property tax.

The House would have removed the exemption for airports from the state property tax, raising $5 million in FY 2010-11. No changes were made to the statewide property tax in the 2009 session.

Impact of Proposals on Tax Fairness

As mentioned above, Minnesota’s tax system has become more regressive over time, and both bodies of the legislature made reversing this trend an explicit goal of their tax bills.

Minnesota cannot make progress on revenue adequacy if all regressive taxes are simply taken off the table. Instead of rejecting a tax package because it contains some regressive elements, the important question instead is whether a tax bill as a whole is progressive. An increase in overall fairness can be achieved by a tax package in which the progressive income tax is large enough to offset the other regressive taxes. Improvements in tax fairness can also be achieved through targeted tax credits to ensure that low-income taxpayers do not shoulder a disproportionate share of taxes.

Both the House and Senate took this approach. Their bills contained changes in the income tax that would make the tax system more progressive. These progressive income tax proposals were big enough that they appear likely to offset the regressive provisions in the bill. Progressive income tax increases made up over half of both bodies’ omnibus tax bills and the two revenue-raising bills developed by the tax conference committee.

Clearly the fourth tier income tax proposals passed by the Legislature would have made the income tax more progressive. In addition, the Senate raised rates on all brackets and the House reformed a large number of tax deductions and credits, noting that the benefit of tax expenditures predominately goes to higher-income households. Analysis by the Minnesota Department of Revenue found that the income tax provisions in both House and Senate omnibus tax bills would have significantly reduced the regressivity of the state’s tax system.[15]

The Senate’s omnibus tax bill proposed raising the statewide business property tax, and was also the origin of the surtax on excess income that was included in the final tax legislation passed by the Legislature. The impact of these proposals is less clear. The surtax on excess income is a new idea, and its impact has not been modeled. However, since higher interest rates are frequently levied on higher-risk loans, it may have a more regressive impact than a general sales tax. And while the Minnesota Department of Revenue’s Tax Incidence Study assumes that business taxes, including corporate taxes and property taxes paid by businesses, are regressive, there is no consensus among economists as to the final incidence of business taxes.

Legislative tax proposals included increases in regressive taxes as well. The House bill included increases in alcohol, tobacco and local sales taxes.

So the big question is whether the income tax provisions in the proposed tax packages were sufficient to outweigh the regressive tax increases, and bring about a net increase in progressivity of the system. More sophisticated modeling would be needed for a more precise figure, but a rough analysis looking at the size of the different tax components and their relative regressivity suggests that the legislative omnibus tax bills, as well as the two tax bills that came out of the tax conference committee, would have made the tax system more progressive.

The Governor did not have rebalancing the tax system as an explicit goal, and since his tax proposal overall was relatively small, it is unlikely it would have had a dramatic impact on the overall regressivity of the tax system. However, his regressive proposal to cut the Renter’s Credit made up over 21 percent of the total impact of his bill, and the entire impact of that proposal lands on low- and moderate-income Minnesotans.

More Tax Debate Lies Ahead

During the 2009 Legislative Session, there was a robust debate about the state’s tax system. Each body of the legislature passed three tax bills that proposed using taxes as part of a balanced approach to the state’s budget shortfall, and throughout the session legislative leaders stated that addressing regressivity in the tax system was a top priority. The Governor held firm to his position that tax increases would not be part of the budget solution. He vetoed the tax increase legislation that reached his desk, and the legislature was unable to override his vetoes.

That meant the session ended with a $2.7 billion deficit remaining, and the Governor took the unprecedented step of addressing this deficit unilaterally through unallotment. But unallotment can only address the budget deficit in the short term; it does not make progress on resolving the longer-term deficit in FY 2012-13. Nor does this outcome allow the state to make progress in rebalancing the tax system. The debate about the appropriate size and structure of the tax system will undoubtedly continue.